THE UPDATE SCOOP (#13/2024)

Defeasibility of Title in Subsequent Purchaser Seemingly in Good Faith with Valuable Consideration

By TAY & HELEN WONG – September 26, 2024

In a split decision of 3 over 2, the Federal Court in Setiakon Engineering Sdn Bhd v Mak Yan Tai & Anor ([2024] 8 CLJ 190), ruled for the original landowner in a case which concerned the issue of indefeasibility of a land title that had been transferred to a subsequent purchaser under s.340 of National Land Code (the NLC) and vested in that purchaser by virtue of s.89 of the NLC.

The land was originally owned by the Respondents/Plaintiffs(P)’ mother (the deceased) since February 1975. One CMK acting as attorney of one LM had filed a legal suit (OS) to claim that the land had been used by LM as collateral for a loan granted to her by the deceased and that the loan had been repaid in full to the deceased but LM had forgotten to re-register the land in her name. A judgment in default (JID) was entered in the OS which granted a declaration that LM was the lawful and beneficial owner of the land. With the JID, CMK was able to obtain a cancellation of the deceased’s title and the issuance of a replacement title in LM’s name as the owner of the land.

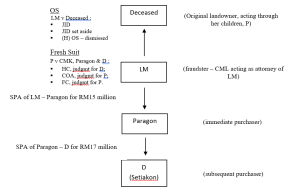

Within a month after the JID, CMK acting as LM’s attorney entered into a sale and purchase agreement with one Paragon Capacity S/B (Paragon) at the price of RM15 million in cash. Within 3 months, the land was transferred to Paragon by LM. Just over 3 months after, Paragon entered into a sale and purchase agreement with the Appellant/Defendant (D) for the sale of the land at the price of RM17 million. Three months thereafter, the land was registered in D’s name. The relationship is depicted in the following chart:

About 2 years after the registration of the land in D’s name, P succeeded to set aside the JID. The hearing of the OS then proceeded in the absence of CMK which resulted in the dismissal of the OS. In May 2019, P filed a fresh suit against CMK, Paragon and D (the said Suit). CMK and Paragon did not appear in the said Suit. As against D, the High Court ruled that D was a bona fide purchaser for value and acquired indefeasible title to the land pursuant to s.340(3) of the NLC. For the benefit of readers, s.340(1) of the NLC confers indefeasibility of title upon the person whose name appears in the register document of title as proprietor but s.340(2) makes the indefeasibility to become defeasible if it is vitiated by any of the circumstances specified thereunder (e.g. fraud, forgery and a void instrument). However, the indefeasibility of the title will be restored under the proviso of s.340(3) if the land is purchased by a subsequent purchaser in good faith and for valuable consideration but not otherwise. D succeeded on this ground.

That decision was however reversed by the Court of Appeal (COA) which held, among others, that the setting aside of the JID rendered LM’s replacement title void ab initio (void at inception) and hence, the titles held by LM, Paragon and D were defeasible and ought to be set aside.

On final appeal to the Federal Court, the panel of five judges by a 3-2 majority affirmed the COA decision. The majority pointed out the effect of the setting aside of the JID was nullifying the court order declaring LM to be the lawful and beneficial owner of the land and destroying the whole substratum of the basis for the cancellation of the deceased’s title and the issuance of the new replacement title. Then, with both CMK and Paragon not contesting the said Suit, fraud had been proven against CMK, thus rendering LM’s title to the land defeasible under s.340(2) and liable to be set aside in the hands of any subsequent purchaser under s.340(3) if the land was not purchased in good faith and for valuable consideration by the subsequent purchaser, which in this case, was D.

The apex court, in the majority, rejected D’s contention that the order setting aside the JID ought not to automatically operate retrospectively in the absence of an explicit order to that effect as per O.42 r.7(2) of the Rules of Court 2012 (ROC2012). In doing so, the court answered the question on “where a judgment in default was set aside but the successful party failed to apply for or obtain an order under O.42 r.7(2) of the ROC2012 that the order should take effect from an earlier date, whether it was justifiable to treat all steps taken during the intervening period (being 3 years in this case) in reliance on the default judgment as null and void or void ab initio”, in the affirmative. This resulted in a “knock-on effect” of nullifying and wiping out all transactions in the land beginning with the fraudulent transfer of the land to LM. Section 89 of the NLC which provides for conclusiveness of title upon registration did not assist D since the land reverted to its pre-cancellation status and by virtue of nemo dat quod non habet (No one can give what he does not have), Paragon could not pass the non-existent right or benefit from the void replacement title to D.

The pinnacle court, in the majority, further held the “conclusive evidence” declaration in s.89 of the NLC did not dispense with the need to carry out due diligence or proper investigation beyond the register document of title. It did not confer indefeasibility of title upon a person which was governed by s.340(1) of the NLC. In considering whether D had proven it was a bona fide purchaser for value, the court took into the few factors:

- The haste in which the transfers of title were carried out from the time the title was registered in LM’s name to the time the land was sold to Paragon which D had every reason to suspect Paragon had no financial capacity to pay the RM15 million cash to LM;

- Despite the substantial price it was paying for the land, D did not even bother to obtain a valuation report to ascertain the market value of the land before proceeding with the purchase which a reasonably prudent purchaser would have taken such an ordinary precaution.

- Good faith demanded more from D than merely to conduct a land search and enquiring from Paragon’s solicitors when and how Paragon acquired the land and requesting for a copy of the Paragon agreement.

In the mind of the majority, D had taken advantage of the “conclusiveness” of title under s.89 and used it as a convenient excuse to turn a blind eye on the suspicious circumstances surrounding the status of the land. Elements of carelessness and negligence negated good faith.

The parting remark of the majority judgment is noteworthy in its highlighting of the modus operandi by fraudsters to conjure a scam to pave the way for a purchaser like D to purchase the land as “subsequent purchaser” with the objective to cleanse the title of the stain that had rendered the land defeasible under s.340(2) of NLC, thus clearing the path for them to make a fortune. It would appear from this decision that an intended “subsequent” purchaser ought to exercise prudence by carrying out due diligence of the vendor’s title which goes beyond conducting normal land search on the register document of title at the land registry and includes “investigation/review” of the previous dealings between the previous purchaser and vendor.

For any query or to subscribe to our UPDATE SCOOP or quarterly published legal bulletin THE UPDATE, please e-mail your request to:

hhtay@thw.com.my or lawpractice@thw.com.my

Tags: [land law] [defeasibility of title] [good faith and valuable consideration] [s.340 National Land Code] [fraudster]